I’ve always been fascinated by fictional works, whether fantastical or not. Not just the final products, but how these fictional works come into being has always been in my field of interest.

Worldbuilding captures my attention for this reason.

I’m currently reading a book called Building Imaginary Worlds (wolf, 2012). I’ll continue examining some chapters of this book, but this entry is about maps, which deserve a special place in the book’s third chapter, “World Structures and Systems of Relationships.”

contents

maps according to Wolf

The author mentions three fundamental features for a world to exist:

- a space in which things exist, and events can occur

- a duration or span of time in which events can occur

- a character or characters who can be said to be inhabiting the world

Some tools enable the creator and subsequently the reader/viewer to organize these fundamental features:

- maps structure space and connect a world’s locations together

- Timelines organize events into chronological sequences and histories

- Genealogies show how characters are related to each other

the oldest and perhaps most common tool used to introduce a world and orient an audience is the map.

The importance of maps is evident both for convincing the reader/viewer of the fiction and as one of the best tools the creator can use during the worldbuilding process. As Tolkien said:

If you’re going to have a complicated story you must work to a map; otherwise you’ll never make a map of it afterwards.

Due to the technologies of their respective periods, maps have a considerable variety. For this entry, I’ll discuss narrative-focused maps of history.

narrative focused maps of “real” history

Due to the many unknown places in the past, maps filled these places with unseen creatures and surround them with buildings difficult even to imagine. All these maps present us with humanity’s perspective on the world across different periods.

Peutinger map – travel focused

“the earliest need to fix places on a map was linked to travel: it was a reminder of the succession of stops, the outline of a journey. It was thus linear in form, and could only be made using a long scroll.”1

A travel-based narrative map showing the entire road network of the Roman Empire. you can check its details here: https://isaw.nyu.edu/exhibitions/space/tpeut.html

modern subway maps use the same logic as the peutinger map. topology over accuracy, prioritizing usability over precision.

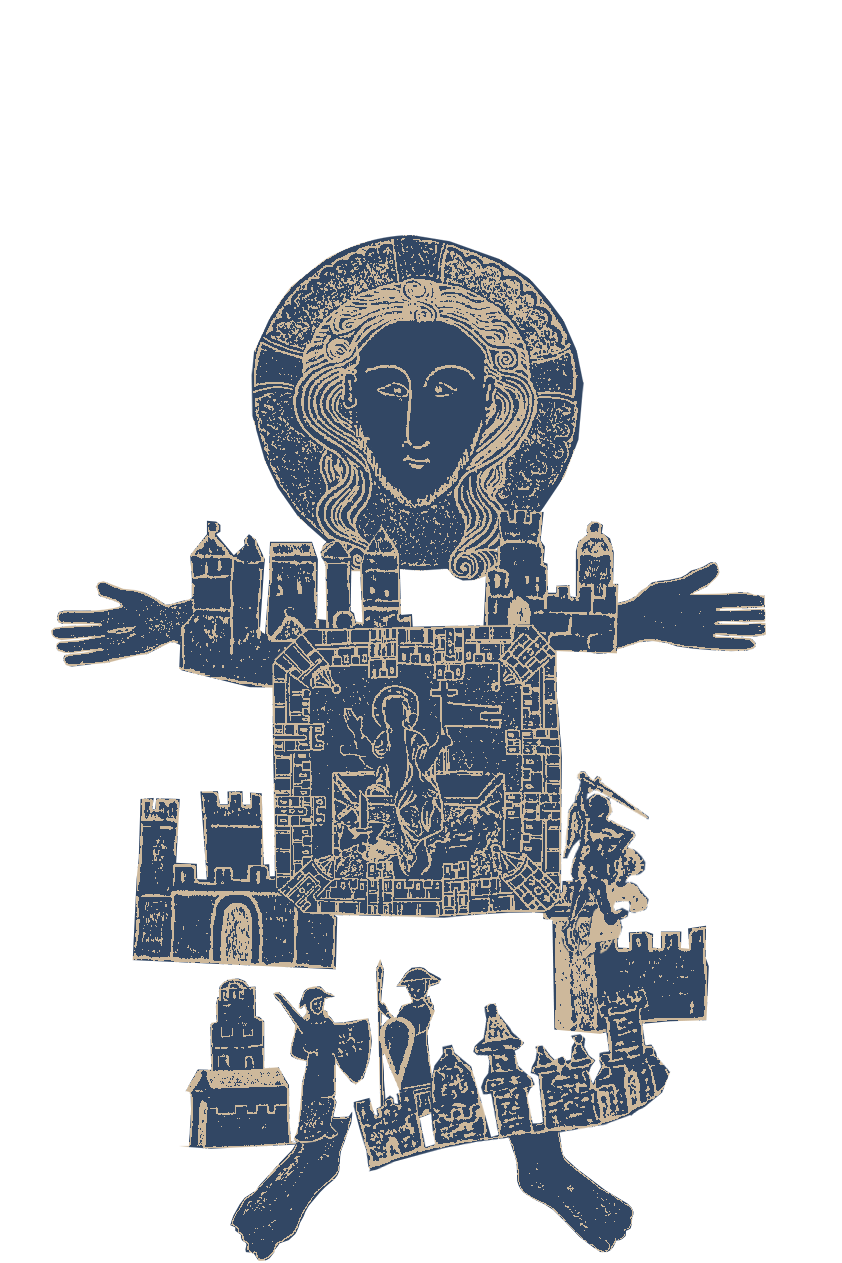

Hereford Mappa Mundi – theologic narrative focused

An encyclopedic world map that visually narrates Biblical stories, paradise, mythological creatures, and religious geography.

if you want to explore this map’s narrative more, you can go to the link: https://www.themappamundi.co.uk/mappa-mundi/

hereford mappa mundi does not answer the question of how to get to a from b, it answers to the relationship of god and where people live. we can see that jerusalem is in the middle of the world.

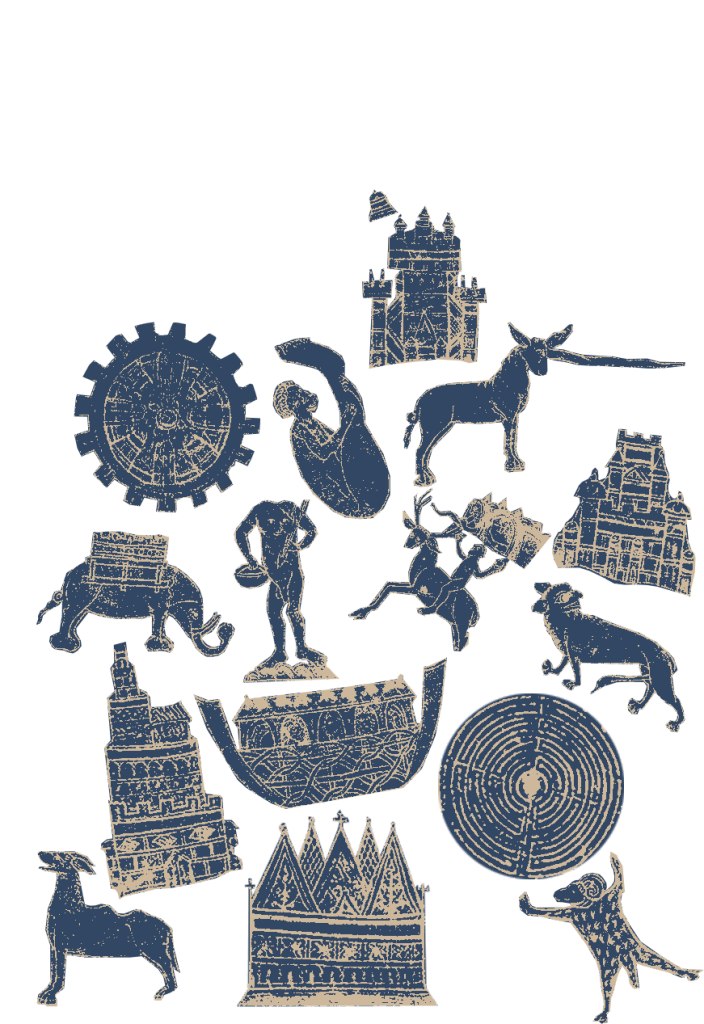

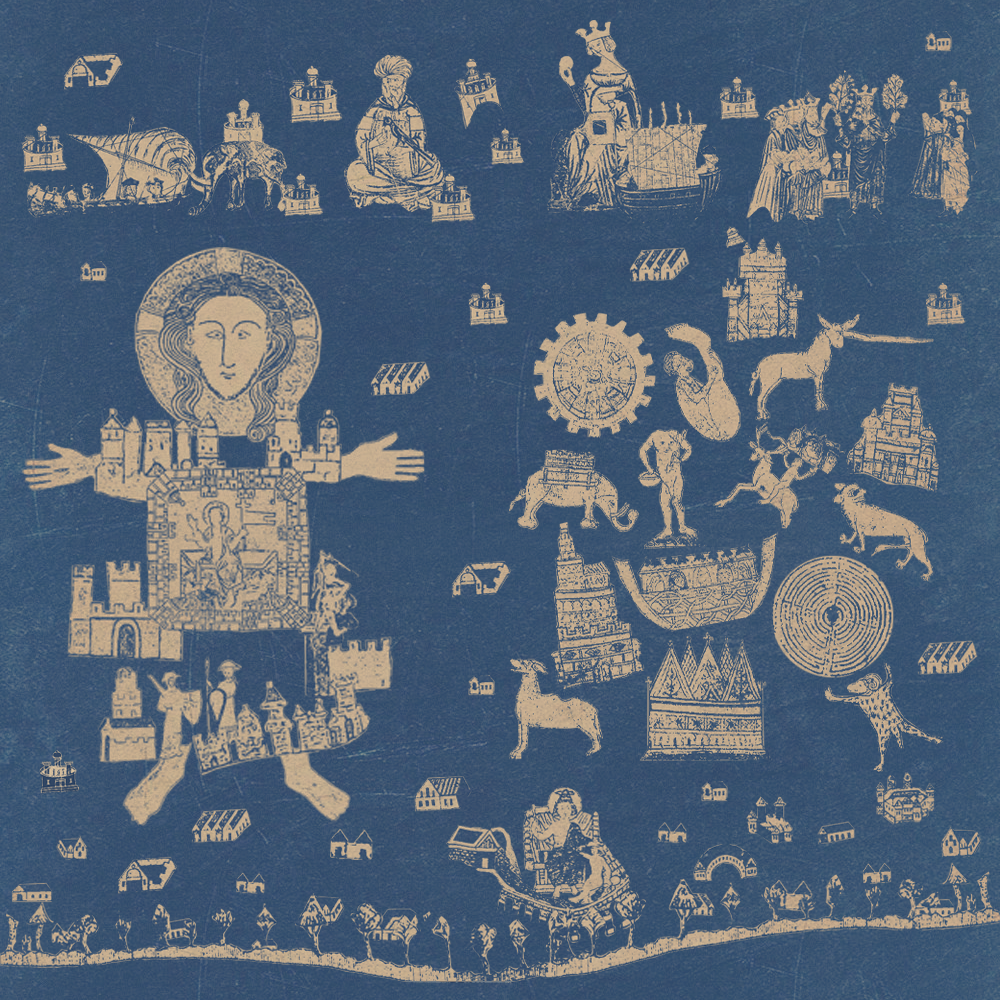

Ebstorf map – theologic narrative focused

The world depicted as the body of Christ; a theological universe design with the head in paradise and hands and feet at the four corners of the world.

the world is christ now, “every place is sacred, “all creation is sacred”.

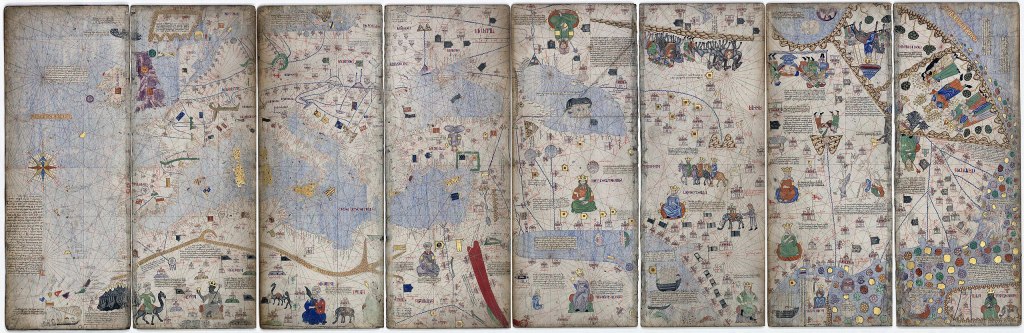

Catalan Atlas – mercantile exploration focused

the world organized around commerce, travel routes, and economic power centers. the map narrates how to navigate and trade across the known world.

we can see the change of question “where is paradise?” to “where is money?”.

even though these maps seem wrong from our point of view now, they are actually perfectly accurate to their purpose. and with each system of mapping the world, these historical maps reveal something crucial: maps have always been telling stories or they were tools to storytelling.

and what happens when the world itself is invented?

in the next entry, i’ll dive into the maps of fantasy literature and how they guide us through lands that never existed.

- Italo Calvino, Collection of Sand, trans. Martin McLaughlin (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2013), p. 18. ↩︎